'Masala' is not quite an alien concept to Bollywood and the Indian Theatre. Spicing things up has been intrinsically the Indian style, in both literature and cinema. From the way we deck up, conduct ourselves or, simply, with what we read and write, there is an element of 'Masala' in everything we do, invariably.

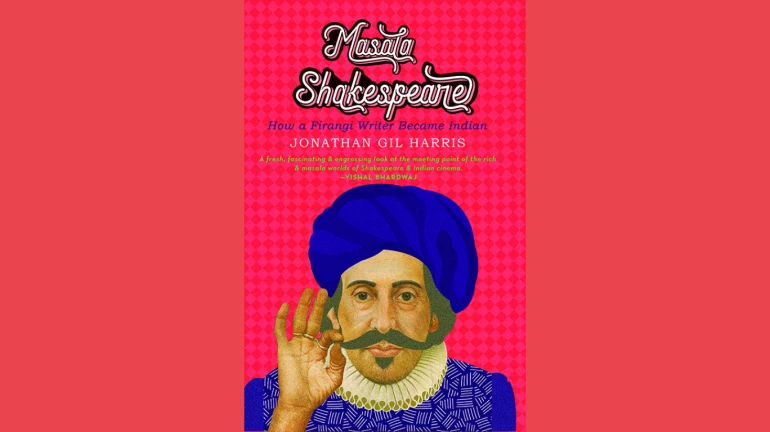

Much inspired by this realistic and relatable idea India dwells on, Jonathan Gil Harris talks about the adaptation of the same in literature, focusing on none other than the most celebrated playwright William Shakespeare, in his latest book ‘Masala Shakespeare’.

Much known as the ‘Firang who turned Indian’, Jonathan, moved to the country 6 years back. Awestruck by the multi-linguistic and the diverse Indian culture, he seems to have fallen in love with the Indian lifestyle, just as it is- crowded. Currently a professor at the Ashoka University, he lives in Delhi and teaches literature.

In a session at the Kala Ghoda Festival 2019, Jonathan said, “My years, living in India, has helped me as a Shakespearean understand an element of Shakespeare that we have been conditioned- thanks to the colonial curriculum- to deny about him; that Shakespeare was an entertainer, producing a certain kind of entertainment that we can call ‘Masala’. And I am not referring simply to Manmohan Desai’s god awful films in the 1980s. I am talking about masala as a more capacious way of thinking that has suffused hindi films since the first hindi talkies were made in the 1930s.”

In an exclusive interaction, Jonathan spoke about his inspiration behind writing the book and his reasons to stay back in India, giving us a sneak peek into his ideologies and his school of thought as a Shakespearean.

Here’s what he had to say:

Talking about Masala Shakespeare, what exactly was the trigger point that inspired you to write a book on how Shakespeare dealt with Masala and how it has been adopted in Hindi films?

"Well, it’s hard to identify the exact moment when I realised that I wanted to write this book but I was in the Chanakya Theatre, watching Lagaan when I realised with a rush of excitement- ‘Oh my god, this is Shakespearean…. Not so much the story of the film, but the experience of being in a large theatre, with people from very very different classes, all of us watching an entertainment that was clearly meant for all of us and not in some sort of Hollywood way, but in a manner that was quite specifically 'Masala'. It was very very Indian but it was, at the same time, weirdly British, in the time of Shakespeare… because Shakespeare was writing for an audience that was extremely mixed, ethnically, linguistically, culturally, religiously… So, there were certain profound commonalities between the Britain Shakespeare’s time and the India in the 20th and 21st centuries. But I think it was because of Lagaan that I fell in love with Hindi cinema. And it was because of Hindi cinema that I started approaching Shakespeare very differently from how I’ve been taught Shakespeare. And that’s one thing led to another… I started teaching Shakespeare very differently and as a result of that and the classes I was teaching… bit by bit I realised that there was something here that needs a larger audience, an audience of not just people who are dutifully studying Shakespeare but also Indians who are bit by bit becoming alienated from the world of the single screen cinema, the genre of masala. And they need to recognise that it is a repository of so much cultural treasure but we’ve learnt to cringe at it."

Besides Lagaan, which other films inspired you to write this book?

"There are so many. I mean I write in the book about Gulzar's ‘Angoor’. I talk about a number of some adaptations like ‘The Taming of the Shrew’, Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s ‘Goliyon ki Rasleela, Ramleela’, 'Ishaqzaade'. There are so many versions of Romeo and Juliet, Rituparno Ghosh’s ‘The Last Lear’. But there are dozens of other films, some of which I love, some of which I don’t love so much. But the idea is not so much to talk about individual films. It’s sort of to capture in all of the colourful variety, this amazing sort of 'masala' tradition that I think we’re losing now."

Living in India for 6 years now, what is it besides films and theatre that inspired you from the Indian culture?

"It’s really hard to identify things but a lot of what I love about India is precisely what a lot of people can’t stand, and they look at me and say, 'What do you mean?' Like for instance, I love how crowded India is. I am a people person but I am also a colour person. I love the idea that there are many ingredients in the mix here. I love that India can’t be reduced to one religion or one language despite the attempts of some political parties. And I think it is a real asset even though so many people say to me ‘But you come from New Zealand. It is such a beautiful country. It’s so small and people live far away from each other and have privacy.’ I’m actually not that vested in privacy."

What is it that you found strikingly different in this transition from New Zealand to India?

"I think the biggest transition was the multi-lingualism and not just in the sense of individual languages that people could speak but also in everyday conversations, when people would keep swerving between different languages. So, I’ve been taught this Hindi that no one’s ever spoken. I studied Hindi for many years in America before I moved here. But I had to unlearn the Hindi that I had been taught because it was a 'shudh' Hindi, totally sankritised and every Urdu, Arabic, Persian term had been perched from it. I remember this one day, I write about it in the book, I just arrived in India and I was feeling fairly confident about my mastery over this Hindi I had been taught. And I was in Delhi University’s North campus, looking for the library and I walked up to someone and I said, ‘Mere mitra, kripya bataiye- pustakalaya kahan hai?’ And he was like- ‘Hain? Aap kahan se aate hain?’ And I said, ‘Main New Zealand se hun’ and I asked him the question again. He looked at me and said, ‘Bohot buri Hindi hai’ and then said, ‘Ah, matlab library?

I realised after speaking to him and then speaking to many other people that the everyday reality of speaking in India involves moving between Urdu, Hindi, English, Bhojpuri at times, Punjabi, definitely Punjabi… and so I had to unlearn the Hindi that I had been taught and pick up this completely impure Hindustani, which meant sort of tuning, not only tuning my ears to different dialects but also recognising that every conversation was also a negotiation where you are working out with the person I am speaking with- Where they come from? What’s their mother tongue? What are they comfortable in? Where can we move together? What is off limits?- And I love that, you know? It means that there are many more conversations in just the explicit conversation going on at once. And the most important part of those other conversations is that I am trying to find a common ground with you. I must say, anywhere I go in India, that people even in Tamil Nadu, even though they love Tamil, they’re constantly moving between Tamil and English and different registers of Tamil; there’s Chennai Tamil, there’s Tamil of Madurai. But every conversation is a negotiation as a result, unless you’re speaking with your family. So, that’s something I feel is a real asset in India and it embarrasses so many Indians now saying ‘Oh, no one knows how to speak Hindi properly. They speak in million languages but they don’t speak Hindi or English properly.’

And I say, come on, that’s how Shakespeare wrote. Shakespeare was moving between Anglo Saxon slang and high French and sort of Latinate English. He had to keep swerving and it was out of that swerving that the most creative forms of expression emerged. That’s been the biggest learning for me."

Can you tell us three words in which you can describe your book... three words which capture the essence of your story?

"It’ll have to be more than three words- ‘India’ and ‘Shakespeare’ bohot ‘Masala’ hai.

In english I would say- ‘Purity is overrated.’"

Talking to Jonathan, one would be inspired to look at his/her immediate surroundings and appreciate the culturally driven aspects which we had been ignoring all this while. And this less acknowledged Indian setup is something that seems to be one of the driving factors for his book ‘Masala Shakespeare’.

We need not be a litterateur or a cinema addict to identify the 'masala' elements Shakespeare used to be creative or how the Indian film industry evolved. As mentioned earlier, spicing things up is just the Indian way of life. It’s high time that we start accepting that there is nothing wrong with it, as long as it brings out the best of creativity.

When a person, not natively from India, can learn to draw such analogies and appreciate art, it’s important that we recognise and treasure the same as Indians.